Today I spent my morning working with the faculty of a local school where the annual tuition is $565 per child. That averages out to about $50 a month. The average teacher’s salary is $490 a month. My maid makes $240 a month and she only works five hours a day; and unlike a teacher, she doesn’t have to assess student work at night or build a creative lesson plan for how she is going to do my laundry the next day. Oh, and I forgot to mention: The school is an accredited International Baccalaureate School.

In my opening session, with the faculty, I asked them this question: What is the goal of a school? Their responses were not much different than what I would have heard from members of the American School of Bombay’s faculty. I wasn’t surprised. After all, teachers, know why we exist. Next, I asked them a series of 15 other questions. These questions ranged from “types of student assessment” to the “role of parents in education” to the “purpose of homework” and I ended the session with 15 minutes on the “impact of professional development on student learning.” Here, with these 15 questions, their answers were very different than what I would have received from a group of ASB teachers.

One of my questions was: How do the structures of your school calendar impact student learning? This led to a discussion around:

- 45 min periods every day vs. 80 min periods every other day.

- Semester grades vs. trimester grades vs. one grade for an annual comprehensive exam.

- The impact the academic year length and the vacation structures have on student learning.

And that’s when I knew what today’s post would be about. It would touch on “school structures.”

Currently schools around the world follow agrarian school calendars, and we have done so for centuries. Here are two data points based on the 10-week summer vacation found in most agrarian calendars:

- Students experience the equivalent of 2.6 months of grade-level equivalency loss in math.

- 85% of teachers spend two-plus weeks at the beginning of the school year re-teaching critical skills forgotten from the previous year.

However, as with any evolution, not everyone agrees with what a School Calendar 2.0 should look like. The unanimous agreement, that our 20th century calendars need to be deconstructed and then super-structured, has opened the provocative conversation about what type of school calendar would best support student learning.

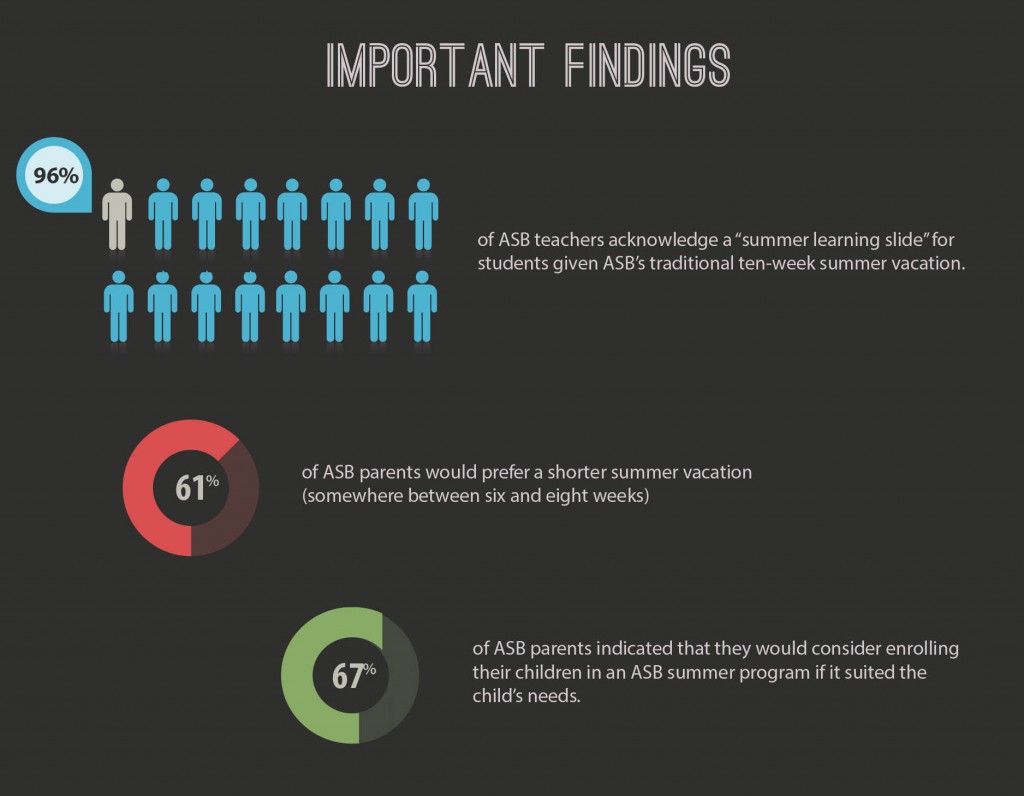

At ASB we are beginning to have this conversation as well. To give us a starting point we sent out a survey last week. Our respondents have given us some fantastic feedback and we have already started digesting it. Here are three points to consider:

The bottom line is: many school structures from yesterday do not meet the needs of today’s families and students. The question is: which structures need to evolve and what should the avatars look like?

The conversation continues…